Introduction

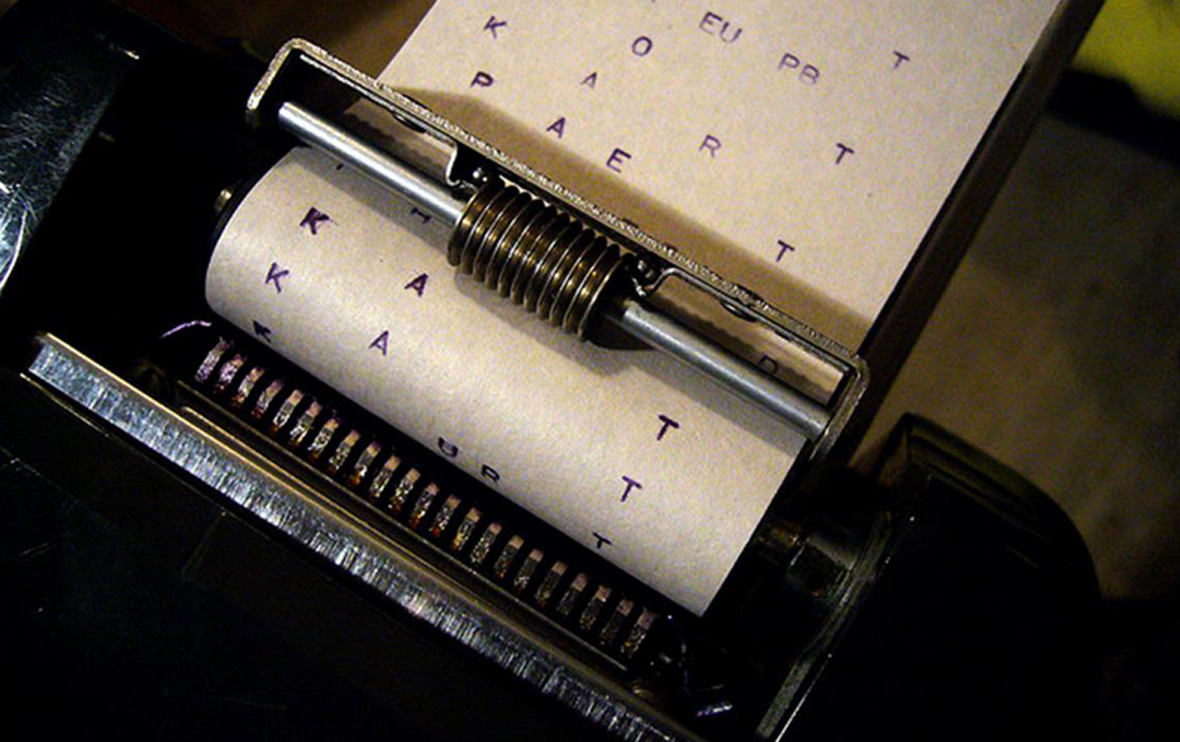

Insurance companies have a number of tools at their disposal to investigate and adjust claims. One of the most powerful tools is the insurer’s authority to require the insured to appear in person to produce documents, physical evidence and answer questions under oath before a court reporter – the so-called Examination Under Oath. Proper conduct of EUOs is essential to an insurer’s efforts to combat fraudulent claims. But at the same time innocent claimants find the EUO process onerous and insurers spend precious time and resources needlessly. Minnesota follows a rule of reasonableness in imposing the obligation to attend an Examination Under Oath.

The Legal Basis for Examinations Under Oath

Insurers in Minnesota are required to have a written anti-fraud plan. Although the cost of defending a fraudulent claim may exceed the amount of the fraud, insurers have a fiduciary duty to their insureds and investors to have a written anti-fraud plan in place to ensure that they actively combat fraudulence.

Minn. Stat. § 60A.954 – Insurance Anti-fraud Plan

An insurer shall institute, implement, and maintain an antifraud plan…

An antifraud plan shall establish procedures to:

(1) prevent insurance fraud, including: internal fraud involving the insurer’s officers, employees, or agents; fraud resulting from misrepresentations on applications for insurance; and claims fraud;

(2) report insurance fraud to appropriate law enforcement authorities; and

(3) cooperate with the prosecution of insurance fraud cases.

The insurance company’s right to include an EUO requirement in its insurance policy is set forth in statute.

Minn. Stat. § 65A.01 – Standard Fire Insurance Policy

The insured, as often as may be reasonably required, shall exhibit to any person designated by this company all that remains of any property herein described, and, after being informed of the right to counsel and that any answers may be used against the insured in later civil or criminal proceedings, the insured shall, within a reasonable period after demand by this company, submit to examinations under oath by any person named by this company, and subscribe the oath.

These sections of Minnesota statutes give the insurance company the legal authority to include EUO requirements in their insurance contracts. Typical language was found in the recent case Western National Insurance Co. v Thompson, 781 N.W.2d 412 (Minn. 2010).

We have no duty to provide coverage under this policy unless there has been full compliance with the following duties:

***

B. A person seeking any coverage must:

1. Cooperate with us in the investigation, settlement or defense of any claim or suit.

***

3. Submit, as often as we reasonably require:

***

b. To examinations under oath and subscribe the same.

Thompson at 415.

As the Thompson court pointed out, courts have upheld EUO requirements in Minnesota since at least 1897 in Hamberg v. St. Paul Fire & Marine Ins. Co., 68 Minn. 335, 337, 71 N.W. 388, 388 (1897). And as early as 1884, the United States Supreme Court recognized the right of insurers to require insureds to submit to examinations under oath “to enable them to decide upon their obligations, and to protect them against false claims.” Claflin v. Commonwealth Ins. Co., 110 U.S. 81, 94–95, 3 S.Ct. 507, 515, 28 L.Ed. 76 (1884).

If the claimant refuses to submit to an EUO, the insurer may deny the claim for failure to cooperate. The insurer has the burden of proving a substantial and material lack of cooperation resulting in substantial prejudice to its position. White v. Boulton, 259 Minn. 325, 107 N.W.2d 370 (1961). Whether the insured has breached the cooperation clause contained in an insurance policy is a question of fact. See, e.g., Caron v. Farmers Ins. Exchange, 252 Minn. 247, 90 N.W.2d 86 (1958). The trial court’s findings on this issue will be affirmed if they are supported by the evidence as a whole and unless they are clearly erroneous. See e.g., Noehl v. Midwest Empire, Inc., 298 Minn. 565, 215 N.W.2d 487 (1974); Juvland v. Plaisance, 255 Minn. 262, 96 N.W.2d 537 (1959).

Reasonable Examinations Under Oath after Thompson

In Thompson the court considered the case of two claimants who claimed injury after a motor vehicle accident and were seeking reimbursement of medical expense and wage loss benefits pursuant to Minnesota’s No-Fault Act. The insurer paid substantial benefits before realizing that one of the claimants was employed by the chiropractor who provided the treatment for which reimbursement was claimed. The claimants refused to attend an EUO and the no-fault arbitrators held the hearings without the benefit of an EUO and awarded the claimants substantially all of the benefits they sought.

The Court determined that the obligation to attend an Examination Under Oath is subject to a standard of reasonableness that is within the no-fault arbitrator’s power to decide. Therefore, the arbitration was awarded.

Insurers do not have an unrestricted right to demand Examinations Under Oath, but insureds run the risk of losing their right to benefits if they fail to cooperate in attending an EUO.

Lessons for Insurers

The lessons of Thompson are clear for insurers. They should chose claimants for examinations under oath carefully, use limited resources wisely, and be ready to articulate a reasonable basis for requiring an EUO to obtain the evidence in question. Preferably, the insurer should be able to articulate how the evidence is not available through any less oppressive investigative device.

Red flags that may trigger an EUO referral include:

Cost of initial treatment

Late bills

Bills to post office boxes

Frequent name changes

Self-referrals

Multiple ownership

Attorney referrals

Red flags continued

Referring relationships

Providing transportation

Inappropriate advertisements

Disproportionate treatment for people involved in litigation

Unusual charges – too high or too low

Unusual or inappropriate treatment considering the patient

Some more red flags:

Block billing

Illegible records

Bills not on HCFA forms

Community reputation

Response from the patient

Disproportionate service to a single non-English speaking community

Providers with translation services

Considerations in Selecting Claims for an EUO

Compare treatment notes to bills to ensure they match.

Look for patterns – treatment, supplies coding, frequency.

Compare the coding to the bills, the bills to the records.

Does the time or amount of supplies charged make sense?

Look for disproportionate payments.

Can you identify who owns the facility?

How hard is it to contact the provider?

How hard is it to locate the patient?

Does the patient resist making a statement?

Does the provider produce complete records easily?

Does the facility look questionable on inspection?

Examining the records and bills.

Is there a pattern of level four or five exams?

Is there other obvious up coding?

Do the codes reflect the face-to-face time actually received by the patient?

Do the records reflect the procedure billed?

Do the diagnostic codes reflect complaints found in the records?

Do the records accurately reflect the patient’s recollection?

More records and billing issues.

Do the records document each treatment or simply repeat vague verbiage?

Do the records repeat themselves?

Are records for different patients suspiciously similar?

Look for obvious errors – children disabled from work, wrong names, wrong patient.

Lessons for Claimants

The insurer’s ability to require an EUO is based in its policy language. Obtain a certified copy of the insurance policy and ensure cooperation with the procedure set forth – but nothing more.

The standard of reasonableness is meant to apply to the demand for an EUO, but the finder of fact will naturally judge which side is being more “reasonable.” The insured’s duty is to demonstrate it is more reasonable than the insurer who is demanding an EUO.

Questions to consider:

Can the information be obtained in other ways?

What is the burden of giving the EUO on the claimant?

Is the time, place and manner of the EUO request reasonable?

Will the insurer agree to defend and indemnify the insured if they determine that the claimant’s care provider billed for treatment that was not rendered?

Conclusion

A generation ago the plaintiff’s bar and insurers fought over the obligation to attend Independent Medical Examinations. Similarly, a standard of reasonableness was read into the duty to attend IMEs. In practice, arbitrators rarely found the claimant breached the duty to attend an IME, but they were reluctant to award benefits unless the IME request was clearly abusive and the IME refusal was clearly proper. After time, the practice of routinely refusing to attend IMEs fell out of fashion and insurers made requests more thoughtfully.

The same dynamic is likely to occur with Examinations Under Oath. An insured may be viewed as having less credibility for refusing to attend an EUO, but the insurers will be held to a high standard of proving the request is reasonable. Insurers are likely to evaluate the cost and benefit of routine EUO demands and return to a more historical pattern of EUO requests focused more carefully on suspected fraudulent claims rather than as a routine investigative tool.

In the meantime, the insurer and claimant are in a race to posture themselves as the most reasonable party whenever a request for an EUO is challenged.